I first came across the work of Jo Spence in an exhibition at Stills Photographic Gallery in Edinburgh in 2016.

The exhibition was haunting and filled with frank realism about cancer and death.

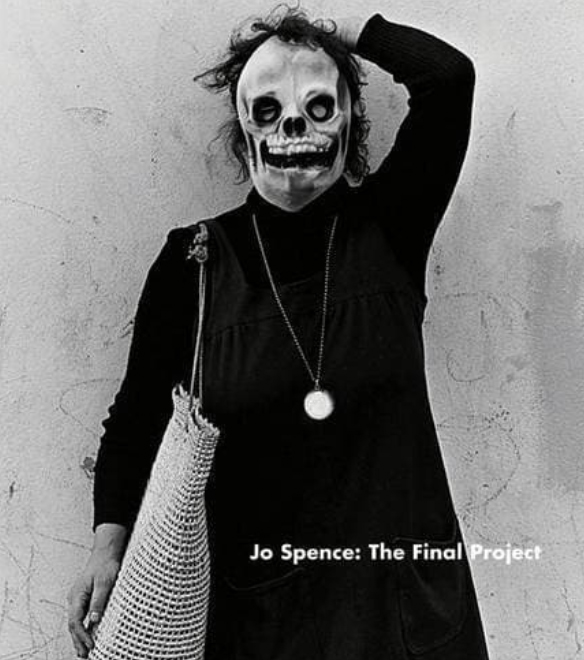

I bought a book at the time, Jo Spence: The Final Project, which shows a small number of photographs from her body of work produced over 2 years when she was suffering from leukemia. (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 11) It gives an account of her final creative work and how Spence dealt with the knowledge that she was dying.

The first striking thing about the book is Louisa Lee’s words in the introduction where she writes of “fascination and avoidance” questioning why she would want to pursue such a project and wondering if she could “circumnavigate the subject” so as to avoid appearing to be too sentimental or sycophantic. (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 12) Lee touches on something which troubles me, the ethics of producing a work on my daughter’s suffering and death when she isn’t here to approve or disapprove of what I am doing. Lee quotes Sontag, “It seems exploitative to look at harrowing photographs of other people’s pain in an art gallery.”(Sontag, 2003, p. 107) These words echo those of Oscan Wilde in a letter sent from Reading Jail and quoted in the unofficial biography of Wilde edited by Rupert Hart-Davis, “For a sentimentalist is simply one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it. You think that one can have one’s emotions for nothing. One cannot.”(Wilde, 1962, p. 501) Although Sontag’s words were written about the terrible things which happen in wars and Wilde’s letter was condemnation and rebuke for his lover, the thrust of the points Sontag and Wilde make would seem to be exactly suited to speaking about or of gazing at photographs of death from a cold and distant viewpoint. This viewpoint is of the spectator or the voyeur. Yet, if the dead are gone, who is best placed to present a version of their lives and their views? Even if in life someone leaves exact set of instructions to be followed to the letter in the event of their death, the dead have no say. Looking at very emotive photographs of the dying and those who have died and experiencing the pain of others second hand is all we can do. The photograph shows what is in the past and we can never go back and live that moment or directly experience someone else’s pain. It is all second hand. I think the question I must ask, is whether experiencing death and trauma second hand, makes it less real or less genuine?

As a small aside, Lee makes another interesting observation. She suggests that there is a difference between looking at a photography on the wall of a gallery or in looking at a photograph in a book. “…the weight and seriousness of such photographs survive better in a book, when one can look privately, linger over the pictures, without talking. Still at some point the book will be closed . The strong emotion will become a transient one.” (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 12) This is very interesting as it speaks to me of how best to allow others to experience my work.

Returning to Spence’s book, Spence died on the 24th June 1992. This was just after her 58th birthday. I mention dates because my own daughter’s birthday was also in June. Such pinpricks of similarity might seem like nothing but to me they make a connection. In some notes she titled, Thoughts on Dying (Being Constructive), dated 5 months before she died which were found after Spence’s death, she comments on her own death and how she would like her funeral to be run and how she would like to be remembered. One which tugs at my heart is where she requests, “I would like my life to be celebrated on my Birthdays (June 15th)” (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 17) I wonder if these notes were found before her funeral or before her next birthday? My daughter also left behind notes and photographs and a certain sense of herself. I find it hard to think of Spence and of my daughter writing these notes when they knew their life was nearing it’s end.

The Memory Box

My daughter left behind a memory box. This box contains things she felt were important. I know if contains some of her hair, shaved off when the chemotherapy started to make it fall out. Beyond that I do not know what is in the box as have never had the courage to open it and feel that sense of space and time rush back. She was 18 when she died and 17 when she found she had cancer so what might she have left? How profound or normal might be the contents of that box? If I don’t look, I never have to find out if there is a sense of disappointment or anger or acceptance in that box. If I don’t look the box contains only posibilities which I feel is a way I can deal with my memory of her. In the back bedroom,, next to the box are school certificates, keepsakes and also hand written notes from her school friends and her school leaver’s book with their comments. Young people confronted by a death of one of their own. How did they make sense of it? Do they still think of her I wonder? Spence quotes George Eliot, “Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them.” (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 23) This is important for my project. Who remembers the countless dead? The worn grave markers overgrown with weeds or those ashes scatters in the wind? Once I am gone, who will remember my daughter? It seems a sad thought but it seems an inevitable fact of life. We all die and unless we happen to be famous, the vast majority of life will pass and leave no trace. Nobody will remember us.

Philomena Epps writes about Spence’s final project towards the end of this book. She says that, “The Final Project is both an exploration of death and confrontation with mortality” and mentions that Spence’s background as a feminist, a socialist and her views on the working class all shaped her perspectives of death. (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 79) Of particular interest in my own work is the idea of “The Shameful Death” which Allan Kellehear speaks of. “Dying has recently become a rather shameful affair – negatively labelled by others…”(Kellehear, 2007, p. 8) and “dying is increasingly becoming an out of sight and mistimed experience” (Kellehear, 2007, p. 213) Importantly for consideration of my own project, Kellehear goes onto speak of the deaths of the young and societal opinion about such deaths which are at the wrong time an can be viewed as difficult and awkward, “the social tragedy and emotional disjunction of a young death in a world where only ‘old people’ are expected to die.” (Kellehear, 2007, p. 214) Epps contrasts death in other cultures such as in Mexico with their celebration of death in the Day of the Dead or even in Western cultures of the past such as in Victorian Britain where death was treated very differently to how death is treated today. Death today where, “the culture of death in Western society to be unspoken , stigmatised and intolerable.” and “ The shunning of death from public gaze has become the norm” (Dennett, Jacob and Tobin, 2013, p. 79). Epps quotes Philippe Ariés who says that death is shunned to “avoid the disturbance and the overly strong and unbearable emotion caused by the ugliness of dying.” (Philippe Aries, 1975, p. 87)

This then is the area my project will explore. It seems to be a minefield of emotional traps and trauma, of remembering things that will be difficult, of reading the works of others and looking at creative works that won’t be easy At same time, at other side of my studies, I hope to have a better, or rather a different, understanding of death and of my own sense of grief.

References.

Dennett, T., Jacob, C. and Tobin, A. (2013) Jo Spence: The Final Project. Ridinghouse.

Kellehear, A. (2007) A Social History of Dying. Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Philippe Aries (1975) Western Attitudes towards Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present: 3 (The Johns Hopkins Symposia in Compative History). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sontag, S. (2003) Regarding the Pain of Others, Nature. New York: Hamish Hamilton for the Penguin Group. doi: 10.1038/361578e0.

Wilde, O. (1962) The Letters of Oscar Wilde. First. Edited by R. Hart-Davis. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.