I went to The Scottish Portrait Gallery to look at the photographic exhibition, Counted: Scotland’s Census 2022.

The exhibition claimed it was “about celebrating who we are. What do we have in common, and what makes us unique?”

Counted: Scotland’s Census 2022

While this exhibition was interesting to me, one set of words struck me as particularly relevant to my research. The audience were told the exhibition is an attempt to put ordinary people into the gallery.

This is interesting as the people depicted in the Portrait Gallery in paintings, photographs and sculptures are normally famous.

It made me think of the vast number of people never photographed or recorded in any way. People who seem to have been airbrushed from life. Their likeness has never been saved or recorded and it is as if they never existed.

Counted: Scotland’s Census 2022

For my project where I been interested in worn and forgotten grave markers, I thought about this on the train home. If people lived lives thought as unremarkable and these people we never recorded in life then what chance is there of them being remembered in death?

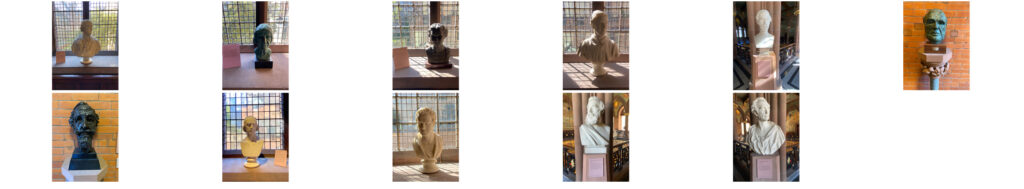

When at the gallery I looked around and snapped some quick images of some of the busts. I have to admit, I don’t know who many of these people were. I also admit that I didn’t stop to read each of the cards that explained who these people were. If I was interested in finding out, I would have to make a conscious effort to research them. In death, even those who have been wealthy or notable such that someone was willing to carve their image and for the Portrait Gallery to collect these busts, might be forgotten. If the busts were in a graveyard they would be overgrown, weather worn, dirty and maybe broken. Maybe acid rain would start to erode the features. Would anybody care? Yet in a gallery setting these people are given a status beyond their deaths. They not completely abandoned. Someone looks after them.

Busts in Scottish National Portrait Gallery

There is another point here which is whether or not the public care? Are graves abandoned as the people who care are limited? Limited by their own lifespan but also by the competing pressures of still being alive? Once we stop living, we matter much less. Who has the time to visit the grave of an unknown relative? I thought of whether the same principles applies to buildings. We die and our possessions are gathered up and passed on or dumped. New people take over that space. Does anything remain of any of us in a building or in a room? Life carries on. The room itself isn’t a shrine.

As I hadn’t been in the gallery since before lockdown, I had a look around for a particular painting my tutor had recommended to me as being relevant to my project.

Three Oncologists by Ken Currie, 2001

The Three Oncologists shows three professors in the field of surgery and molecular oncology. An interesting quotation from Currie on this painting is that in a discussion with one of subjects in his painting, Currie tells us, “When I had a brief discussion with Sir David Lane about the nature of cancer, he said that people saw cancer as a kind of darkness and their job is to go in there and retrieve people from it, from the darkness as it were.” (Currie, 2001) This idea of darkness is interesting to my work. Death can be seen as darkness. Not just a physical darkness as when we placed in a box or buried at sea. But also a sense of being forgotten. A darkness as in a lack of illumination . A lack of interest. Is light only for the living?

Unknown Man by Ken Currie, 2019

I found a second work by Currie, The Unknown Man. This painting shows a forensic anthropologist posed over a body under a green sheet. Currie quotes Professor Sue Black describing her work as an anthropologist, “reconstructs the life led” and “to reunite the identity constructed during a life with what remains or the corporeal form in death.” (Currie, 2019) I was intrigued here about anthropology trying to fill in the unknowns of death.

There appears to be a link between these two paintings by Currie. The oncology doctors trying to pull the living back from the darkness of cancer which leads towards death and the anthropologist, later in the cycle, looking at the body after death and by trying to reconstuct that life, pulling death towards the light.

Very interesting works. I note that the dead and the still living cancer patient are just implied in these paintings as only the doctors are shown. There is a stong link here with my own research and in looking into the darkness and finding a suitable way to reinvent those who are beyond the care of the oncologist or the anthropologost. Those who, if I was to get a spade and split the turf and dig into the ground, might have no form left, no coffin, no shroud, maybe not even any bones. If gravestone has also worn and they have no form and no name, then these vanished people, just as in Currie’s work, are implied.

Photography, can give these people back a visual presense and a new meaning.