When selecting images and ordering these images for my major project I stopped to consider the balance between the visual content and appeal of my work and how my work helps to define and sits within my narrative. What is the meaning and significance of my visual choices both for my ‘straight’ pieces and for my more conceptual work? My work is visual but in describing my choices, in writing an introduction for my project and in giving my work titles, I use words. Do the words I choose add depth to my visual artwork or do they lessen the impact of my visual works? And do the words and the image provide synonymy or can my words introduce the possibility of alternate polysemous messages? An interesting way of considering exhibited work is given in a work on Photovoice Exhibitions which says, “Photographs are a powerful means of portraying the findings of research.” (Latz and Mulvihill, 2017, p. 119) In the research I conducted in my studies, the ultimate use of words has been in my dissertation looking at the photograph used at or near the point of death. While my dissertation came to a written conclusion, how might I represent such a conclusion using visual representation? As the artist/researcher, I am the person who made choices for my written work as I am the person who made choices for the creation of my art. Is that enough and can we assume that my visual works in this project reflect the conclusion to my research? The conclusion to my dissertation was that the photograph as a liminal object was ideally placed to allow us to engage with death. It allows us to construct and maintain memories of those we have lost even if what is recorded by the camera is very different from the reality of how we remember and recall memories. If I turn this around, then do the words in my research portray the ideas contained in my artwork? If not, then must I consider adding more words? Either to my artworks, to the descriptions of my project and titles, or even to my dissertation. I wonder how many words I could use to adequately describe my creative work in this exhibition which caps my undergraduate studies. Does the answer fit somewhere between the bookends of my dissertation and the refusal to provide any words to explain my work and insisting that the audience derive their own meaning from the visual work? It seems straightforward to conclude that words are necessary if I consider the promotion of my work, exhibitions, interviews, newspaper articles, requests for funding, applications for artist residencies and more whether this might be for the purpose of publicity, for audience interest or sales. An alternative is never to print work or present it to anyone else in which case explanation and titles would never be required. Having decided that some kind of text is required and expected of me, then I need to consider how many words and which words and, beyond that, the size of the text and the choice of font and colour. If I were to use as many words as were used in my dissertation then it would be a rare audience member who would have the time or inclination to spend the time required with my project. If I use just a few words to hint at a potential meaning then I need to find something subtle which doesn’t signpost my work or dulls my intention. John Berger begins his book “Ways of Seeing”, “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak” (Berger, 1972, p. 7). Does this imply that in writing the dissertation before this final major project, this was in the wrong order? I wonder if the child does indeed have language before they learn the language of their parents, the gurgles, crying, shrieks and wails all have meaning. Linguist Ferdinand de Saussure defined the physical sign, whether in the form of written or spoken language, as the signifier. The message was signified to the audience.(ref). Roland Barthes took forward Saussure’s concept beyond linguistics and suggested that “The language of narrative” goes beyond the sentence and that the audience played a role. “beyond the sentence are only more sentences – having described the flower, the botanist is not to get involved in describing the bouquet.”(Barthes, 1977, pp. 82–83) Barthes went on to describe the text contained in advertising imagery, telling us that the image‘s first message is linguistic, which is supported by the caption. The second message is the connotation of the message which draws on the knowledge and experience of the viewer. The third part of the message is the medium which acts as itself. If using a photograph as a medium, then this photograph cannot be separated from the message. (Barthes, 1977, pp. 33–35) Crucially for my purpose in trying to decipher how much writing should accompany my images and what words to use, Barthes describes the words which accompany images as being “parasitic”. The image does not illustrate the words, the words take the lead role in defining and fixing the meaning of the picture. (Barthes, 1977, p. 25)

In terms of my degree study, I can see the logic of learning how to research, think logically and present ideas in the form of words before we refine and condense ideas and words to a visual representation of an idea. To that visual representation, some words are added in the briefest form. These words can be viewed as aids for the audience, helping to provide an insight into or an understanding of the artwork, but as Barthes implies, we must be wary when choosing words to accompany images. This isn’t just a matter of giving away the ending. Artists can find the choice of titles problematic as shown by the fact that artificial intelligence title generators for artworks can be found online. Articles also suggest that a strong title can help with the sale of artwork. (Losina, no date; Wilton, 2014) Having said all of this, some artists reject the idea that their works must be titled. I am less interested in sales than in how the text adds or detracts from my visual work. Roland Barthes writes about press photography, “Connotation, the imposition of second meaning on the photographic message” He lists different ways such connotations are imposed. The text which accompanies the photograph is another connotation. (Barthes, 1977, pp. 20–25) It is clear that the text is not inert and influences the viewer. This perhaps explains why some artists reject words to accompany their art.

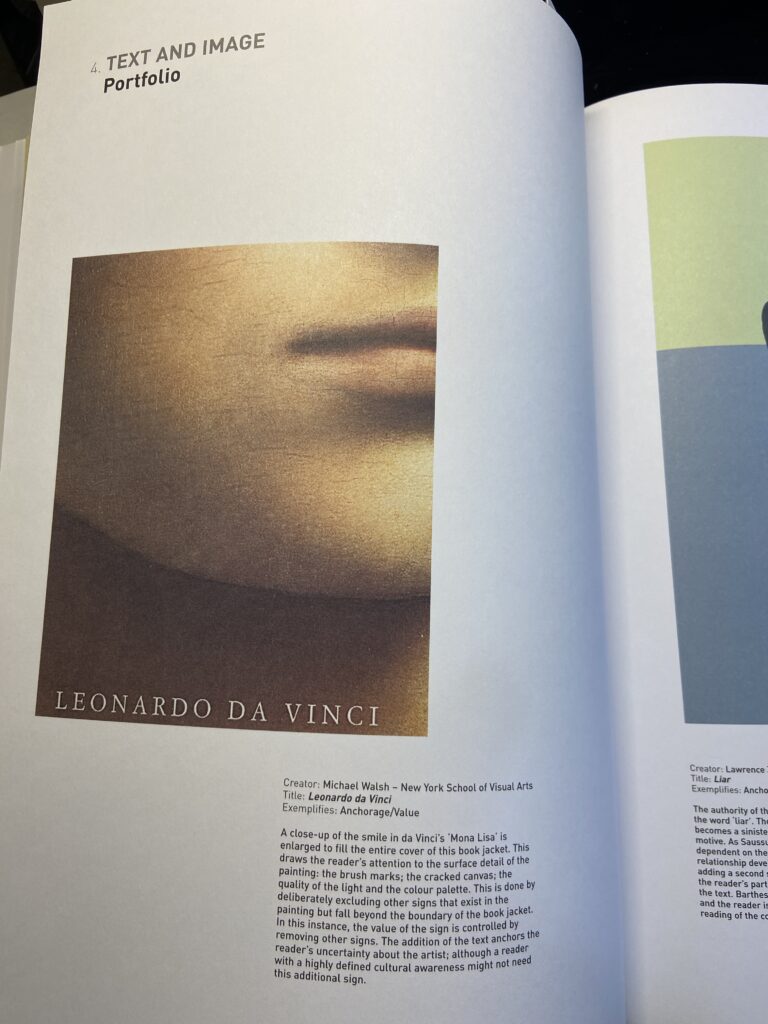

How does my work, which deals with emotions and ideas expressed visually, fit within semiotics? I wonder if the answer might lie in levels and depths. Each artistic project or single work of artwork has different levels of meaning. How do we use art to convey a message? I found a great example of stripping away signs to focus attention on details.

In the image author David Crow tells us that the enlargement of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in Michael Walsh’s book, “draws the reader’s attention to the surface detail of the painting: the brush marks, the cracked canvas, the quality of the light, and the colour palette. This is done by deliberately excluding other signs that exist in the painting but fall beyond the boundary of the book jacket.” (Crow, 2010, p. 76)

There is an element of Crow’s description which, in the words of Barthes, could be seen as parasitic on the purity of the closeup of da Vinci’s painting. Even Michael Walsh, who created the book, adds the text, LEONARDO DA VINCI” in capital letters. Does even this title corrupt and influence the image? Lots to keep in mind then about how images word along side text.

References

Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books.

Crow, D. (2010) Visible Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics in the Visual Arts. London: Fairchild Books.

Latz, A. and Mulvihill, T. M. (2017) Photovoice Research in Education and Beyond: A Practical Guide from Theory to Exhibition. Oxford: Routledge.

Losina, O. (no date) How to title your artwork so it sells, Prima Materia Art Institute. Available at: https://www.primamateriainstitute.com/article/how-to-title-your-art (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

Wilton, N. (2014) How to Title Your Art so it Sells. Available at: https://www.nicholaswilton.com/2014/08/06/how-to-title-your-art-so-it-sells/ (Accessed: 20 November 2024).