I should point out that the backward gaze is a certain look which appears in my creative test pieces and is a look over the shoulder, almost a look of regret or questioning. Crucially, in my work, this is a gaze from the liminal space. From there to here. From them to us.

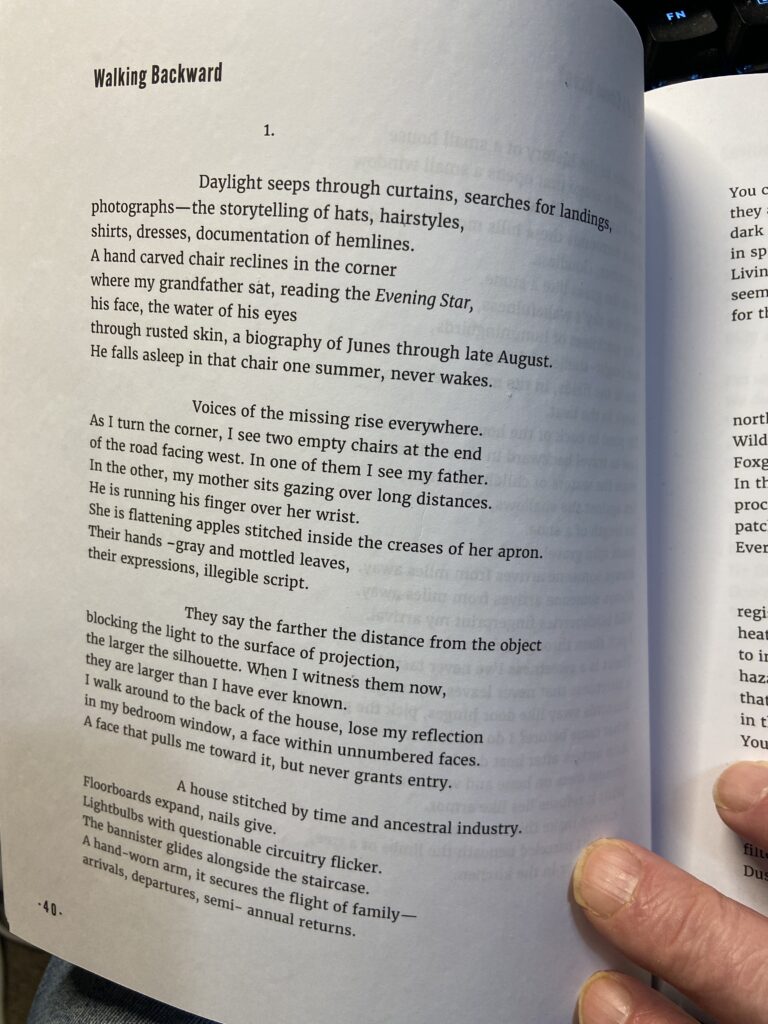

There is a poem called “Walking Backward” by Mitchell Untch which sums up some of my thoughts of this concept. (Untch, 2023, pp. 40–42)

I was researching other artists who have worked with loss or grief and in particular with the liminal threshold. I wanted to know more about their work in this field. There are some very famous artists whose work asks questions in this area.

Tracey Emin’s work, “My Bed”, showing her bed in which she stayed in for 4 days after having a breakdown. When she got out of her bed, she spoke of looking backwards at her bedroom, “Oh, my God. What if I’d died and they found me here?” (Schnabel, 2006) Emin looks back at her bedroom and has a revelation. A what if moment. As well as the thought of her death she envisioned the bed in a white space in a gallery setting. [1] This interests me on two levels. Firstly, that sense of looking back at our own past actions, at mementos of older relatives or friends and in particular of those who are no longer living. This retrospective of our lives and of the lives of others and the sense of looking back is something I have explored in my own work. It speaks of two places or points of view. Of looking from one space to the other. It often seems to come with a very emotional sense of longing or regret. Emin’s practice often seems to be centred around her private life and this backward gaze looks at the inanimate objects in her sleeping space posing questions about Emin and about modern culture through objects which act in her place. She raises question of if she had died. Would this bed then have become a shrine or memorial and the shock of viewers concerned over how she lived her life and of whether this is an unsuitable memorial? The second point of interest is in removing her bed from its natural home setting and moving it to the clean, white, sterile space of an art gallery. With my interest in death studies this space immediately made me think of the mortuary.

Another artist who uses this sense of looking back from the abyss or the liminal space is Ken Currie and his work, “Three Oncologists”. Currie places people in the space to which we look back. This creates a very different sense than does Emin’s objects. I try and imagine what those people are doing, what they are thinking in that space. How do I as a viewer appear from their perspective? There is a sense in these works that something is going on which we cannot be a part of. Each artwork removed the subject from their context, and environment. The bed is placed in a large gallery space without the normal things which make it a bedroom. The surgeons are placed against a dark background outside the operating theatre, with no nurses or other medical professionals and crucially without the patient. As Victoria Crowe says of this work, “There is another layer in this painting… the iconography of mystery and ritual which the figures share make them almost priest-like; they glow against the unfathomable space. Their knowledge keeps them apart from us, a little like mediaeval monks who, being literate, had access to libraries containing the amassed learning of their world.” (Crowe, 2021) Am struck by Crowe’s insight that the doctors are “priest-like” with knowledge permitted to a select few. This knowledge and familiarity could be said to be knowledge of the liminal threshold of death. The ‘priest-like’ can be imagined as a state of mind which aligns with what I said about the sterility and inaccessibility of the mortuary.

The scale of these works is also worth commenting on. Emin’s bed is life sized. Currie’s painting measures 1.95m x 2.44m and in its frame 2.0m x 2.5m. There is something uncompromising about the scale of these works which holds our attention. The ambiguity of these works asks questions of the audience but provides no easy answers even though the questions are framed in such a grand scale.

These artists capture a sense very different from ‘normal’ space, set apart from the normal flow of time and where the laws of nature seem to work differently. This feeling is what I get when working with old album photographs where the original context has been lost, the people are strangers, their stories a mystery waiting to be reinvented. The backward gaze looking directly at us and not allowing us to be passive observers. At the same time, when we look, we bring our own preconceptions, expectations, likes and fears and in looking from our vantage point. There is a balance between the backward gaze and what we see. This balance works as a plane at the liminal threshold.

Francesca Woodman’s photographs work at this boundary, yet she shows us images of herself rather than of objects associated with her or images of other people such as Currie’s oncologists. She invites us to view her blurred, fragmented and ghostlike compositions which have a real sense of punctum for me, in no small part because of her suicide at the age of 22. As an audience we are left with questions she cannot answer other than through the works she left behind. Woodman often avoided the intensity of eye contact although I can find examples of her looking into the lens, these are not the images I most associate with her. I wonder if I might be imposing my gaze over her work. This is the difficulty in engaging with art and trying to remain inert or to recognise the things I bring to the looking which don’t exist in the artwork itself. Harriet Riches’ Ph.D. essay on the Self-Representational Photography of Woodman states that Woodman’s photographs capture the “process of disappearance, as if a subject in flight” (Riches, 2004, p. 15). Riches goes on to describe Woodman’s work and how she follows a similar part as followed by Roland Barthes who wrote of himself having his picture taken and the feeling of experiencing “a micro-version of death” and of “becoming s specter.” (Barthes, 1981, p. 14). Woodman’s self-portraits, whether blurred or her head or face severed by the positioning of the edge of the frame or with mirrors or objects in the frame, could be said to be about absence. Riches asks if Woodman is “drawing attention to the transitional moment of objectification as described by Barthes.”(Riches, 2004, p. 18) These ideas of absence and transition aligned with the inescapable fact of Woodman’s death, place her work firmly at the liminal boundary.

[1] I had a kind of mini nervous breakdown in my very small flat and didn’t get out of bed for four days. And when I did finally get out of bed, I was so thirsty I made my way to the kitchen crawling along the floor. My flat was in a real mess- everything everywhere, dirty washing, filthy cabinets, the bathroom really dirty, everything in a really bad state. I crawled across the floor, pulled myself up on the sink to get some water, and made my way back to my bedroom, and as I did, I looked at my bedroom and thought, ‘Oh, my God. What if I’d died and they found me here?’ And then I thought, ‘What if here wasn’t here? What if I took out this bed-with all its detritus, with all the bottles, the shitty sheets, the vomit stains, the used condoms, the dirty underwear, the old newspapers- what if I took all of that out of this bedroom and placed it into a white space? How would it look then?’ (Schnabel, 2006)

References

Barthes, R. (1981) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Vintage Books.

Crowe, V. (2021) My Favourite Scottish Work of Art, Fleming Collect: Scottish Art News. Available at: https://www.flemingcollection.com/scottish_art_news/news-press/my-favourite-scottish-work-of-art-victoria-crowe-184 (Accessed: 5 May 2024).

Riches, H. K. (2004) The Self-Representational Photography of Francesca Woodman. University College London.

Schnabel, J. (2006) ‘Tracey Emin Interview’. Lehmann Maupin. Available at: moz-extension://7dbcc703-cba0-40a4-9916-0fc8d7aff0cb/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lehmannmaupin.com%2Fattachment%2Fen%2F5b363dcb6aa72c840f8e552f%2FNews%2F5b364ddda09a72437d8ba45e.

Untch, M. (2023) Memorial with Liminal Space. Tampa, Florida: Driftwood Press.